The core of all GSA methods is the comparison between a query dataset (gene list or gene rank) and an annotated database (pathway database, gene set database, or annotated ontology). Most GSA software give the user one or more options to choose a database, with KEGG and GO being the most common options; however, our study may also need a database not included in the software, or a more recent version of the database, or we may want to explore additional databases, and, therefore, some knowledge of the existing alternatives (and some minor bioinformatics work) may be useful. In this post I will briefly review such databases.

Pathway databases:

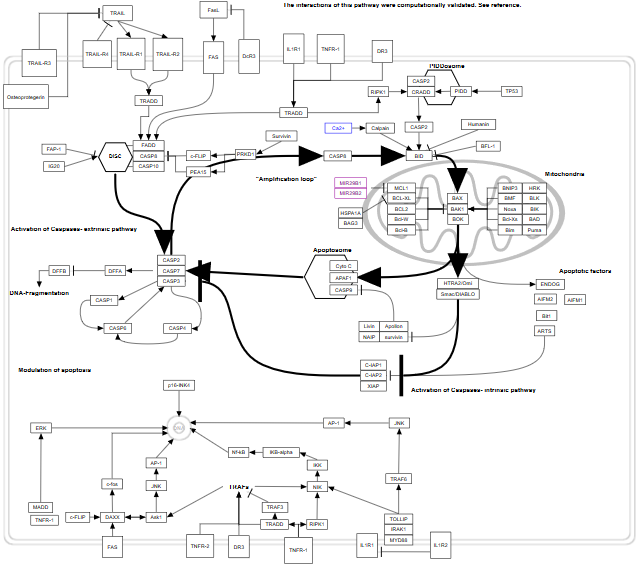

A biological pathway can be defined as a series of interactions or chemical reactions among biomolecules that leads to one or more products. In graphical terms, a pathway is a directed graph of interactions or reactions. In another sense, a pathway is just an interesting part of a biological network and, therefore, the definition of what a pathway is may depend on a curator’s decisions of assigning a certain starting and ending point, a given level of detail (intermediate reactions), and the inclusion or not of pathway cross-talk. Therefore, pathways may look slightly different according to the source database.

There are many pathway databases, but the most popular are, arguably: KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) (1), Reactome (2), and Wikipathways (3). The KEGG database is the eldest of its kind. KEGG Pathway offers visualization of pathways as static flow diagrams made of boxes and arrows, whose style is widely used in the biomedical literature. The Reactome database is a growing resource which is open and provides multiple interfaces, ranging from web-based dynamic visualization (https://reactome.org/PathwayBrowser/) to a downloadable graph database (https://reactome.org/dev/graph-database). It is also highly annotated (up to the individual reaction level). To this date, it has 23,002 pathways, 2,171 of them human. While KEGG and Reactome are curated by their teams, Wikipathways is a community effort that allows submission and curation of pathways from the community. Finally, it is important to mention “Pathway Commons” (4), a resource that acts as a pathway search engine. It allows search by pathway name or gene, and reports all pathways containing the query terms from multiple databases.

KEGG is still the most popular pathway database in history (according to citations), although Reactome is becoming an equally attractive option. However, it has been reported in several occasions that no database is comprehensive enough and that they all have different number and definition of pathways, as well as different numbers of compounds and reactions per pathway (5-7). For this reason, pathway data integration is an important issue. This has proven to be a highly problematic task, although there are some interesting approaches such as “graphite”, which combines four pathway databases in a network of pathways (8). However, instead of integrating databases, gene set analysis users more commonly use databases independently and integrate analysis results.

A few reviews of pathway databases have also been written (see, for example, (9-11)).

A pathway from WikiPathways

Ontology databases:

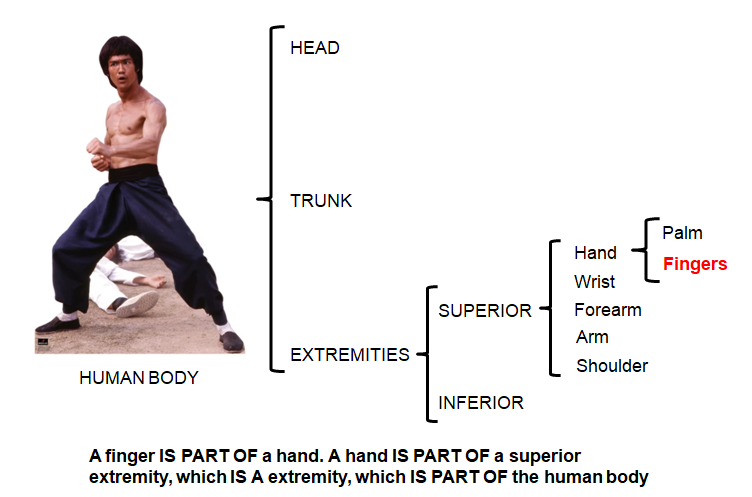

An ontology can be defined as a formal system for describing knowledge, which includes the terms in a certain field, their precise definition, and conceptual relationships among them (such as “is-a” or “part-of”). There are several biological ontologies, including the “Gene Ontology” (GO) (12), “Disease Ontology” (DO) (13), “Human Phenotype Ontology” (14), and many others, which can be discovered using ontology search services such as the “Ontology Lookup Service” (OLS) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ols/index). When ontology terms are annotated with gene information, such as in GO, they become the most commonly used resource for GSA.

The Gene Ontology (GO) is a set of biological terms/concepts/classes that can be applied to genes, gene products or gene functions, as well as the relationships between these concepts. It is composed of: A dictionary (containing the definition of the terms involved in molecular and cell biology), an ontology (a formal system to describe the terms), and a map between genes and GO terms (GO annotation). GO terms are hierarchically organized, from more general terms to more specific terms. At the top of the hierarchy, there are three basic ontologies: biological process (pathways and larger processes), cellular component (localization of gene products), and molecular function. Each term in the GO tree may have multiple parents or multiple children, and each child is related to its parents by relationships such as “is-a”, “part-of”, “regulates”, “occurs-in”, or “capable-of”. For example, “cellular process” (child) is-a “biological process” (parent). GO annotations are descriptions of the function and localization of specific gene products by creating links between gene names and GO terms. They can be created manually by curators or automatically. GO has a very detailed code for the different types of evidence recorded, ranging from EXP (inferred from experiment) to IC (inferred by curator) and IEA (inferred from electronic annotation). The detailed list of GO evidence codes can be found in their website (www.geneontology.org/page/guide-go-evidence-codes).

Ontologies 101

Gene-set databases:

A “gene set” is a simpler and more general concept. Any list of genes that can be grouped for any reason can be defined as a gene set. For example, a group of genes differentially expressed (DE) in a given disease. An annotated ontology (such as GO), the list of genes in a pathway, or a group of phenotypically-related genes, may be gene sets as well.

Some examples of gene set databases are “GeneSetDB” (15), “MSigDB” (16) and “PAGED” (17). GeneSetDB contains several pathway databases (including Reactome and Wikipathways), disease/phenotype databases, drug/chemical databases, gene regulation databases, and the GO. MSigDB contains a series of sub-collections, such as: Positional gene sets (gene set per human chromosome and cytogenetic band), curated gene sets (chemical and genetic perturbations, canonical pathways, Biocarta, KEGG, Reactome), motif gene sets (miRNA targets, TF targets), computational gene sets (cancer gene neighborhoods and modules), GO, oncogenic signatures, and immunologic signatures.

Functional Association Networks:

Functional Association Networks (FAN) are networks that integrate different types of source data such as pathway, co-expression, genetic interaction, protein interaction, and others. The nodes in such networks represent genes or gene products, while the edges represent the probability or degree of belief that those genes are functionally related. Some examples are: FunCoup (18) and GeneMania (19). FANs are mainly used as a reference dataset for a new class of gene set analysis methods (including NEA, EnrichNet, CrossTalkZ, NetPEA, and BinoX) that relies on network interaction.

Unstructured sources of knowledge:

Biomedical literature may contain more pathway information than any existing biological database. However, reading the literature is a task that would take humans a prohibitive amount of time. Therefore, we need methodologies to automatically extract gene-set knowledge from the literature. “Text mining” tools have been developed for many years (20) and they are out of the scope of this review, but it would be interesting to discuss at least one example. MELODI (http://www.melodi.biocompute.org.uk/) is a text mining tool that extracts mechanisms of disease based on subject-predicate-object triples from SemMedDB (Semantic Medline Database) (21). Using a database of triples for the biomedical literature, MELODI is able to link information from different papers and reconstruct the pathways for us. The text mining approach (MELODI+MedSemDB) is less taken into account nowadays, but the growth of the literature and the improvement of the text mining tools may lead us to consider it as another important source of gene set annotation.

R databases:

Several of the above-mentioned pathway, ontology, and gene-set databases do exist as R packages, making it easier to integrate with the different R GSA methods. Examples of R databases are KEGGREST, reactome.db, and others.

KEGGREST allows access to the KEGG REST API. Some basic commands:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

library(KEGGREST)

query <- keggGet("hsa:10458")

query[[1]]

query[[1]]$DEFINITION

query[[1]]$PATHWAY

query2<- keggGet("hsa05130")

query2[[1]]

query2[[1]]$NAME

query2[[1]]$GENE

query3 <- keggGet("hsa05130", "image")

library(png)

writePNG(query3, "imagepath.png")

reactome.db is an R dataset with Reactome information. Some basic commands:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

library(reactome.db)

xx <- as.list(reactomeEXTID2PATHID)

xx['100']

yy <- as.list(reactomePATHID2EXTID)

yy['R-HSA-114608']

zz <- as.list(reactomePATHID2NAME)

zz['R-HSA-114608']

GeneSetDB can be found in the Bioconductor package EGSEAdata. Some basic commands:

1

2

3

library(EGSEAdata)

egsea.data()

gsetdb.human[[3]]

MSigDB can be found in multiple R packages. However, RData files can be downloaded from here: http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/MSigDB/ Among them, the “c2” dataset is one of the most used.

Two Bioconductor packages with ontology data (but not the gene annotation) are GO.db and DO.db. GO.db is a Bioconductor annotation package with Gene Ontology information. For example:

1

2

3

library(GO.db)

xx <- as.list(GOTERM)

xx[['GO:0000001']]

DO.db is a Bioconductor annotation package with Disease Ontology information. For example:

1

2

library(DO.db)

DOTERM[['DOID:0014667']]

However, in order to get the GO annotation, you would need a package like biomaRt:

1

2

3

library(biomaRt)

ensembl = useMart("ensembl", dataset="hsapiens_gene_ensembl")

genes <- getBM (attributes = c('hgnc_symbol', 'ensembl_transcript_id', 'go_id'), filters = 'go', values = 'GO:0000002', mart = ensembl)

Adding your own gene sets:

Finally, if you have your own gene sets, you may build R gene set objects with them and share them with the scientific community. Building an RData object would be enough, but it would be even better if you can store them in the same format used by the previous databases, which can be recognized by some GSA tools. In addition, tools for building gene sets have also been developed; see, for example, GSEABase (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/GSEABase/inst/doc/GSEABase.pdf).

Discussion and thoughts:

As I said in the beginning, sometimes you may want to go beyond the databases offered by the GSA tool that you are using. Choosing a new database resource depends on which kind of information are you looking for (specific pathways? functions in the “Biological Process” Gene Ontology? specific disease association? all of them?). In general, we must keep in mind that pathways contain structural information than gene sets lack, and gene sets contain much more information than just pathways. In addition, in pathways, some genes can be up-regulated and some down-regulated at a given time, while gene sets may change in a coordinated fashion (either all genes up-regulated or down-regulated in a given disease, for example). It has been already discussed that some methodologies were designed to detect coordinated changes, and therefore researchers should be aware of that when choosing a pair of a GSA method and an annotated database (22). In general, over-representation analysis (ORA) and functional class scoring (FCS) methods work with gene set databases (including pathways), pathway databases are necessary for pathway topology based (PT) methods, while FANs are necessary for network interaction (NI) methods.

In any case, it is always important to take into account the trustworthiness and number of gene sets in the database, if they are open or proprietary, and how well they link to advanced GSA and visualization software. For that reason, even though “Pathguide” (23) lists “702 biological pathway related resources and molecular interaction related resources” (http://www.pathguide.org), the truth is that just a few resources are frequently used.

Current databases are highly incomplete and, therefore, before thinking about more sophisticated GSA analytical methods, it is wise to pay attention to having the right type of gene sets, in a good amount/coverage, and with a good quality. It has been said (in the context of machine learning) that “More data beats clever algorithms” and “Better data beats more data” (https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1020712). In the functional interpretation of biomedical data, we could also claim that no GSA method will give us the biological insights we are looking for if we don’t pay enough attention to the amount and the quality of the information contained in the annotation databases that we are using.

References

- Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):29-34.

- Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017.

- Pico AR, Kelder T, van Iersel MP, Hanspers K, Conklin BR, Evelo C. WikiPathways: pathway editing for the people. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(7):e184.

- Cerami EG, Gross BE, Demir E, Rodchenkov I, Babur O, Anwar N, et al. Pathway Commons, a web resource for biological pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D685-90.

- Soh D, Dong D, Guo Y, Wong L. Consistency, comprehensiveness, and compatibility of pathway databases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:449.

- Stobbe MD, Houten SM, Jansen GA, van Kampen AH, Moerland PD. Critical assessment of human metabolic pathway databases: a stepping stone for future integration. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:165.

- Altman T, Travers M, Kothari A, Caspi R, Karp PD. A systematic comparison of the MetaCyc and KEGG pathway databases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:112.

- Sales G, Calura E, Cavalieri D, Romualdi C. graphite - a Bioconductor package to convert pathway topology to gene network. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:20.

- Bauer-Mehren A, Furlong LI, Sanz F. Pathway databases and tools for their exploitation: benefits, current limitations and challenges. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:290.

- Wittig U, De Beuckelaer A. Analysis and comparison of metabolic pathway databases. Brief Bioinform. 2001;2(2):126-42.

- Chowdhury S, Sarkar RR. Comparison of human cell signaling pathway databases–evolution, drawbacks and challenges. Database (Oxford). 2015;2015.

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25-9.

- Schriml LM, Arze C, Nadendla S, Chang YW, Mazaitis M, Felix V, et al. Disease Ontology: a backbone for disease semantic integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D940-6.

- Groza T, Kohler S, Moldenhauer D, Vasilevsky N, Baynam G, Zemojtel T, et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology: Semantic Unification of Common and Rare Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(1):111-24.

- Araki H, Knapp C, Tsai P, Print C. GeneSetDB: A comprehensive meta-database, statistical and visualisation framework for gene set analysis. FEBS Open Bio. 2012;2:76-82.

- Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdottir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(12):1739-40.

- Huang H, Wu X, Sonachalam M, Mandape SN, Pandey R, MacDorman KF, et al. PAGED: a pathway and gene-set enrichment database to enable molecular phenotype discoveries. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13 Suppl 15:S2.

- Alexeyenko A, Sonnhammer EL. Global networks of functional coupling in eukaryotes from comprehensive data integration. Genome Res. 2009;19(6):1107-16.

- Mostafavi S, Ray D, Warde-Farley D, Grouios C, Morris Q. GeneMANIA: a real-time multiple association network integration algorithm for predicting gene function. Genome Biol. 2008;9 Suppl 1:S4.

- Raychaudhuri S, Schutze H, Altman RB. Using text analysis to identify functionally coherent gene groups. Genome Res. 2002;12(10):1582-90.

- Kilicoglu H, Shin D, Fiszman M, Rosemblat G, Rindflesch TC. SemMedDB: a PubMed-scale repository of biomedical semantic predications. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3158-60.

- Tarca AL, Bhatti G, Romero R. A comparison of gene set analysis methods in terms of sensitivity, prioritization and specificity. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79217.

- Bader GD, Cary MP, Sander C. Pathguide: a pathway resource list. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D504-6.